The climate in Bhutan is extremely varied, which can be attributed to two main factors-the vast differences in altitude present in the country and the influence of North Indian monsoons.

Climatic Zones of Bhutan

Southern Bhutan has a hot and humid subtropical climate that is fairly unchanging throughout the year. Temperatures can vary between 15-30 degrees Celsius (59- 86 degrees Fahrenheit). In the Central parts of the country which consists of temperate and deciduous forests, the climate is more seasonal with warm summers and cool and dry winters. In the far Northern reaches of the kingdom, the weather is much colder during winter. Mountain peaks are perpetually covered in snow and lower parts are still cool in summer owing to the high altitude terrain.

Seasons

Bhutan has four distinct seasons in a year.

The Indian summer monsoon begins from late-June through July to late-September and is mostly confined to the southern border region of Bhutan. These rains bring between 60 and 90 percent of the western region's rainfall. Annual precipitation ranges widely in various parts of the country. In the Northern border towards Tibet, the region gets about forty millimeters of precipitation a year which is primarily snow. In the temperate central regions, a yearly average of around 1,000 millimeters is more common, and 7,800 millimeters per year has been registered at some locations in the humid, subtropical south, ensuring the thick tropical forest, or savanna.

Bhutan's generally dry spring starts in early March and lasts until mid-April. Summer weather commences in mid-April with occasional showers and continues to late June. The heavier summer rains last from late June through late September which are more monsoonal along the southwest border.

Autumn, from late September or early October to late November, follows the rainy season. It is characterized by bright, sunny days and some early snowfalls at higher elevations.

From late November until March, winter sets in, with frost throughout much of the country and snowfall common above elevations of 3,000 meters. The winter northeast monsoon brings gale-force winds at the highest altitudes through high mountain passes, giving Bhutan its name - Drukyul, which means Land of the Thunder Dragon in Dzongkha (the native language).

Average Temperatures in Bhutan

It should be noted that average temperatures are recorded from valley floors. There can be considerable divergences from the recorded figures depending upon elevation.

| Month | Values in Celsius | Paro | Thimphu | Punakha | Trongsa | Bumthang | Mongar | Trashigang |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | Max | 9.4 | 12.3 | 17.0 | 13.0 | 10.08 | 15.5 | 20.4 |

| Min | 9.4 | 12.3 | 17.0 | 13.0 | 10.08 | 15.5 | 20.4 | |

| February | Max | 13.0 | 14.4 | 19.0 | 13.9 | 10.0 | 15.9 | 21.7 |

| Min | 1.5 | 0.6 | 7.8 | 0.4 | -1.4 | 8.3 | 11.5 | |

| March | Max | 14.5 | 16.4 | 22.8 | 16.7 | 16.2 | 20.0 | 24.8 |

| Min | 0.6 | 3.9 | 10.4 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 11.6 | 14.4 | |

| April | Max | 17.6 | 20.0 | 26.2 | 20.1 | 18.7 | 22.8 | 28.3 |

| Min | 4.6 | 7.1 | 12.9 | 6.6 | 3.9 | 14.0 | 17.0 | |

| May | Max | 23.5 | 22.5 | 29.1 | 21 | 21.3 | 25.1 | 30 |

| Min | 10.6 | 13.1 | 17.7 | 11.6 | 9.5 | 17.4 | 22.6 | |

| June | Max | 25.4 | 24.4 | 29.2 | 22.2 | 22.5 | 26.1 | 30.7 |

| Min | 14.1 | 15.2 | 20.1 | 13.6 | 13.5 | 19.5 | 22.6 | |

| July | Max | 26.8 | 25.9 | 30.4 | 25.3 | 24.1 | 27.1 | 31.5 |

| Min | 14.9 | 15.6 | 20.5 | 15.3 | 13.6 | 19.8 | 23.1 | |

| August | Max | 25.3 | 25.0 | 29.1 | 23.8 | 23.0 | 25.4 | 30.2 |

| Min | 14.7 | 15.8 | 20 | 15 | 13.7 | 19.6 | 22.7 | |

| September | Max | 23.4 | 23.1 | 27.5 | 22.6 | 21.6 | 24.7 | 30.0 |

| Min | 11.7 | 15 | 19.1 | 14.2 | 12.1 | 19.4 | 21.9 | |

| October | Max | 18.7 | 21.9 | 26.1 | 21.8 | 19.5 | 22.7 | 29.1 |

| Min | 7.4 | 10.4 | 14.7 | 11.7 | 5.9 | 15.8 | 17.7 | |

| November | Max | 13.9 | 17.9 | 22.6 | 19.8 | 16.1 | 19.9 | 26.1 |

| Min | 1.4 | 5.0 | 9.6 | 6.4 | -0.5 | 11.2 | 13.6 | December | Max | 11.2 | 14.5 | 19.1 | 18.2 | 12.3 | 17.7 | 23.0 |

| Min | -1.7 | -1.1 | 6.3 | 2.5 | -2.3 | 9.5 | 11.6 |

The country was originally known by many names including Lho Jong, ‘The Valleys of the South’, Lho Mon Kha Shi, ‘The Southern Mon Country of Four Approaches’, Lho Jong Men Jong, ‘The Southern Valleys of Medicinal Herbs and Lho Mon Tsenden Jong, ‘The Southern Mon Valleys where Sandlewood Grows’. Mon was a term used by the Tibetans to refer to Mongoloid, non-Buddhist peoples that populated the Southern Himalayas.

The country came to be known as Druk Yul or The Land of the Drukpas sometime in the 17th century. The name refers to the Drukpa sect of Buddhism that has been the dominant religion in the region since that period.

Initially Bonism (a pre-buddhist religion of Tibet) , was the dominant religion in the region that would come to be known as Bhutan. Buddhism was introduced in the 7th century by the Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo and was further strengthened by the arrival of Guru Rimpoche, a Buddhist Master that is widely considered to be the Second Buddha.

The country was first unified in 17th century by Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyel. After arriving in Bhutan from Tibet he consolidated his power, defeated three Tibetan invasions and established a comprehensive system of law and governance. His system of rule eroded after his death and the country fell into in-fighting and civil war between the various local rulers. This continued until the Trongsa Penlop Ugyen Wangchuck was able to gain control and with the support of the people to establish himself as Bhutan’s first hereditary King in 1907. His Majesty Ugyen Wangchuck became the first Druk Gyalpo (Dragon King) and set up the Wangchuck Dynasty that still rules today.

In 2008 Bhutan enacted its Constitution and converted to a democracy in order to better safeguard the rights of its citizens. Later in November of the same year, the current reigning 5th Druk Gyalpo Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck was crowned.

The kingdom of Bhutan lies deep in the eastern Himalayas. It is surrounded by the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) of China to the north, and the Indian territories of Assam and West Bengal to the south, Arunachal Pradesh to the east and Sikkim to the west. The tiny landlocked kingdom has a total area of 46,500 km² and spreads between meridians 89°E and 93°E, and latitudes 27°N and 29°N.

The altitude zones of Bhutan

The relief of Bhutan can be divided into three altitude zones, namely, the the Greater Himalayas of the north, the hills and valleys of the the Inner Himalayas, and the foothills and plains of the Sub-Himalayan Foothills.

1. The Greater Himalayas

The towering Himalayan mountains of Bhutan dominate the north of the country, where peaks can easily reach 7,000 metres (22,966 ft) above the sea level. Some of the best known peaks are Jiwuchudrakey and Jumo Lhari. Permanent snow, glaciers and barren rocks form the main features of this zone. These snowy, glacial high lands are the sources for many of the rivers of Bhutan. At a little higher altitude, you will reach the tree line, the point where the vegetation changes from forest into small bushes of juniper and rhododendrons.

2. The Inner Himalayas

Rising continuously from the lower foothills to a height of about 4000 metres, the valleys of different heights and topography makes the country an ideal place for both native people and tourists within the mainland of Bhutan. The valleys of Bhutan are traversed by the country’s five major river systems and their tributaries which ultimately drain to the Brahmaputra River in India. The valleys are linked by a series of passes (called "La" in Dzongkha, the national language of Bhutan). Between the Haa valley and Paro valley is the Chele La (3,780 metres (12,402 ft), the highest pass crossed by a Bhutanese highway. The Lateral Road from Thimphu to Punakha crosses the Dochu La (3,116 metres (10,223 ft)), which features 108 chortens (stupas) built to commemorate the expulsion of Assamese guerrillas. To the east of Wangdue Phodrang is the Pele La (3,390 metres (11,122 ft)). Continuing to the east along the main highway, other major passes include the Yotang La, Thrumshing La and Kori La (2,298 metres (7,539 ft).

The vegetation in this zone is a mixture of broad-leaved and coniferous forest.

3. The Sub-Himalayan Foothills

Stretched along the southern border of the country, the Duar Plain drops sharply away from the Himalayas into the large tracts of sub-tropical forest, grasslands and bamboo jungle. The altitude of the southern foothills ranges from about 200 metres at the lowest point to 2000 metres. This zone is rich in dense and sub-tropical vegetation.

People

Bhutanese people can be generally categorized into three main ethnic groups. The Tshanglas, Ngalops and the Lhotshampas.

Tshanglas

The Tshanglas or the Sharchops as they are commonly known as, are considered the aboriginal inhabitants of eastern Bhutan. According to historians, Tshanglas are the descendants of Lord Brahma and speak Tshanglakha. They are commonly inhabitants of the eastern part of the country. Weaving is a popular occupation among their women and they produce beautiful fabrics mainly of silk and raw silk.

Ngalops

The Ngalops who have settled mostly in the six regions of western Bhutan are of Tibetan origin. They speak Ngalopkha, a polished version of Dzongkha, the national language of Bhutan. Agriculture is their main livelihood. They cultivate cereals such as rice, wheat, barley and maize along with a variety of other crops. They are known for Lozeys, or ornamental speech and for Zheys, dances that are unique to the Ngalops.

Lhotshampas

The Lhotshampas have settled in the southern foothills of the country. They speak Lhotshamkha (Nepali) and practice Hinduism. Their society can be broken into various lineages such as the Bhawans, Chhetris, Rai’s, Limbus, Tamangs, Gurungs, and the Lepchas. Nowadays they are mainly employed in agriculture and cultivate cash crops like ginger, cardamom and oranges.

The other minority groups are the Bumthaps and the Khengpas of Central Bhutan, the Kurtoeps in Lhuentse, the Brokpas and the Bramis of Merak and Sakteng in eastern Bhutan, the Doyas of Samtse and finally the Monpas of Rukha villages in WangduePhodrang. Together the multiethnic Bhutanese population number just over 700,000.

Society

Bhutanese society is free of class or a caste system. Slavery was abolished by the Third King Jigme Dorji Wangchuck in the early 1950s through a royal edict. Though, a few organizations to empower women were established in the past, Bhutanese society has always maintained relative gender equality. In general our nation is an open and a good-spirited society.

Living in Bhutanese society generally means understanding some accepted norms such as Driglam Namzha, the traditional code of etiquette. Driglam Namzha teaches people a code of conduct to adhere to as members of a respectful society. Examples of Driglam Namzha include wearing a traditional scarf (kabney) when visiting a Dzong or an office, letting the elders and the monks serve themselves first during meals, offering felicitation scarves during ceremonies such as marriages and promotions and politely greeting elders or seniors.

Normally, greetings are limited to saying “Kuzuzangpo” (hello) amongst equals. For seniors and elders, the Bhutanese bow their head a bit and say “kuzuzangpo la” (a more respectful greeting). Recently, shaking hands has become an accepted norm.

The Bhutanese are a fun-loving people fond of song and dance, friendly contests of archery, stone pitching, traditional darts, basketball and football. We are a social people that enjoy weddings, religious holidays and other events as the perfect opportunities to gather with friends and family.

The openness of Bhutanese society is exemplified in the way our people often visit their friends and relatives at any hour of the day without any advance notice or appointment and still receive a warm welcome and hospitality.

Religion

The Bhutanese constitution guarantees freedom of religion and citizens and visitors are free to practice any form of worship so long as it does not impinge on the rights of others. Christianity, Hinduism and Islam are also present in the country.

Buddhism

Bhutan is a Buddhist country and people often refer to it as the last stronghold of Vajrayana Buddhism. Buddhism was first introduced by the Indian Tantric master Guru Padmasambhava in the 8th century. Until then the people practiced Bonism, a religion that worshiped all forms of nature, remnants of which are still evident in some remote villages in the country.

With the visit of Guru Padmasambhava, Buddhism began to take firm roots within the country and this especially led to the propagation of the Nyingmapa (the ancient or the older) school of Buddhism.

Phajo Drugom Zhigp from Ralung in Tibet was instrumental in introducing yet another school of Buddhism – the Drukpa Kagyu sect. In 1222 he came to Bhutan, an event of great historical significance and a major milestone for Buddhism in Bhutan, and established the DrukpaKagyu sect of Buddhism, the state religion. His sons and descendants were also instrumental in spreading it to many other regions of western Bhutan.

By far the greatest contributor was Zhabdrung Nawang Namgyal. His arrival in 1616 from Tibet was another landmark event in the history of the nation. He brought the various Buddhist schools that had developed in western Bhutan under his domain and unified the country as one whole nation-state giving it a distinct national identity.

The Buddhism practiced in the country today is a vibrant religion that permeates nearly every facet of the Bhutanese life style. It is present in the Dzongs, monasteries, stupas, prayer flags, and prayer wheels punctuate the Bhutanese landscape. The chime of ritual bells, sound of gongs, people circumambulating temples and stupas, fluttering prayer flags, red robed monks conducting rituals stand as testaments to the importance of Buddhism in Bhutanese life.

Animism

Though Bhutan is often referred to as the last Vajrayana Buddhist country, you can still come across animistic traditions and beliefs being practiced by the people.

The form of Buddhism practiced in Bhutan has absorbed many of the features of Bonism such as nature worship, worship of a host of deities, invoking and propitiating them. According to Bonism, these deities were the rightful owners of different elements of nature. Each different facet of nature was associated with its own specific type of spirit.

or example, mountain peaks were considered as the abodes of guardian deities (Yullha), lakes were inhabited by lake deities (Tshomem), cliff deities (Tsen) resided within cliff faces, the land belonged to subterranean deities (Lue and Sabdag), water sources were inhabited by water deities (Chu giLhamu), and dark places were haunted by the demons (due).

Every village has a local priest or a shaman to preside over the rituals. Some of the common forms of nature worship being practiced are the Cha festival in Kurtoe, the Kharphud in Mongar and Zhemgang, the BalaBongko in WangduePhodrang, the Lombas of the Haaps and the Parops, the JomoSolkha of the Brokpas, the Kharam amongst the Tshanglas and the Devi Puja amongst our southern community.

These shamanistic rituals are performed for various reasons ranging from to keep evil spirits at bay, bring in prosperity, to cure a patient or to welcome a new year.

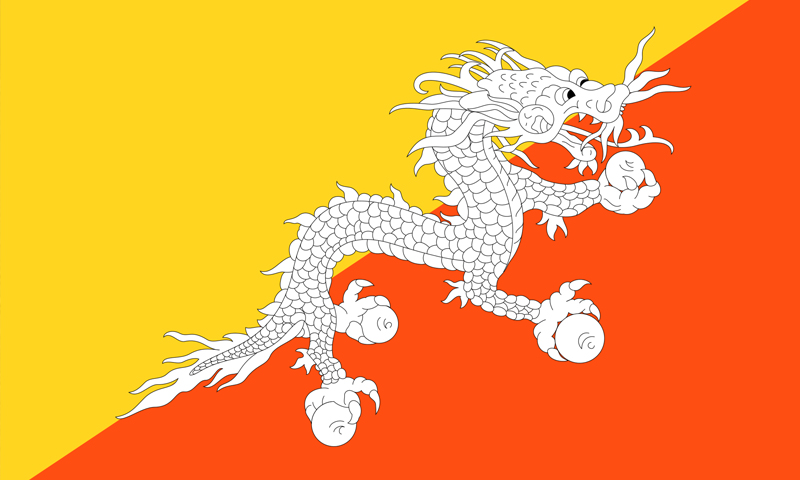

The National flag is divided diagonally into two equal halves.

The upper half signifies the secular power and authority of the king and the lower half symbolizes the practice of religion and the power of Buddhism, manifested in the tradition of Drukpa Kagyu. The dragon signifies the name and the purity while the jewels in its jeweled claws stand for the wealth and perfection.

The national sport is the Archery (Dha). The bow and arrow play a significant role in many Bhutanese myths and legends; images of the gods holding a bow and arrows are considered especially favorable.

The National Emblem of Bhutan is a circle that projects a double diamond thunderbolt placed above the lotus.

There is a jewel on all sides with two dragons on the vertical sides. The thunderbolts represent the harmony between secular and religious power while the lotus symbolizes purity.

The national bird is the raven. It adorns the royal crown. The raven represents the deity Gonpo Jarodongchen (raven headed Mahakala), one of the chief guardian deities of Bhutan.

The national animal is the Takin (Burdorcas.taxicolor) that is associated with religious history and mythology. It is a very rare mammal with a thick neck and short muscular legs. It lives in groups and is found above 4000 meters on.the north- western and far north eastern parts of the country. They feed on bamboo. The adult Takin can weigh over 200 kgs.

The national flower is the Blue Poppy (Meconopsis Grandis).

It is a delicate blue or purple tinged blossom with a white filament. It grows to a height of 1 meter, and is found above the tree line (3500-4500 meters) on rocky mountain terrain. It was discovered in 1933 by a British Botanist, George Sherriff in a remote part of Sakteng in eastern Bhutan.

The national tree is the cypress (Cupressus torolusa).

Cypresses are found in abundance and one may notice large cypresses near temples and monasteries. This tree is found in the temperate climate zone, between 1800 and 3500 m. Its capacity to survive on rugged harsh terrain is compared to bravery and simplicity.

Bhutan is linguistically rich with over nineteen dialects spoken in the country. The richness of the linguistic diversity can be attributed to the geographical location of the country with its high mountain passes and deep valleys. These geographical features forced the inhabitants of the country to live in isolation but also contributed to their survival.

The national language is Dzongkha, the native language of the Ngalops of western Bhutan. Dzongkha literally means the language spoken in the Dzongs, massive fortresses that serve as the administrative centers and monasteries. Two other major languages are the Tshanglakha and the Lhotshamkha. Tshanglakha is the native language of the Tshanglas of eastern Bhutan while Lhotshamkha is spoken by the southern Bhutanese of Nepali origin.

Other dialects spoken are Khengkha and Bumthapkha by the Khengpas and Bumthap people of Central Bhutan. Mangdepkah, which is spoken by the inhabitants of Trongsa and the Cho Cha Nga Chang Kha which is spoken by the Kurtoeps. The Sherpas, Lepchas and the Tamangs in southern Bhutan also have their own dialects. Unfortunately two dialects that are on the verge of becoming extinct are the Monkha and the Gongduepkha.

The most distinctive characteristic of Bhutanese cuisine is its spiciness. Chillis are an essential part of nearly every dish and are considered so important that most Bhutanese people would not enjoy a meal that was not spicy.

Rice forms the main body of most Bhutanese meals. It is accompanied by one or two side dishes consisting of meat or vegetables. Pork, beef and chicken are the meats that are eaten most often. Vegetables commonly eaten include Spinach, pumpkins, turnips, radishes, tomatoes, river weed, onions and green beans. Grains such as rice, buckwheat and barley are also cultivated in various regions of the country depending on the local climate.

The following is a list of some of the most popular Bhutanese dishes:

Ema Datshi

This is the National Dish of Bhutan. A spicy mix of chilies and the delicious local cheese known as Datshi. This dish is a staple of nearly every meal and can be found throughout the country. Variations on Ema Datshi include adding green beans, ferns, potatoes, mushrooms or swapping the regular cheese for yak cheese.

Momos

These Tibetan-style dumplings are stuffed with pork, beef or cabbages and cheese. Traditionally eaten during special occasions, these tasty treats are a Bhutanese favourite.

Jashu Maru

Spicy minced chicken, tomatoes and other ingredients that is usually served with rice.

Red Rice

This rice is similar to brown rice and is extremely nutritious and filling. When cooked it is pale pink, soft and slightly sticky.

Shakampaa

Shakam paa is a wonderful Bhutanese food of dried beef cooked with dried chilies and sometimes slices of radish.